James came in to Window Studio a couple of weeks ago. After first wanting maybe a portrait of himself and his wife of 20 years for their soon-to-be new home, or then maybe one of the grandkids (though he was only my age and looked younger), he then said what he’d really like was one of his mother. Even though by now I have come to expect that most men who come in – and it is mostly men that come in – want a portrait of their mothers, the way James spoke about his mother particularly moved me. He said he didn’t think that she could come in to sit because she had been quite sick lately. He said she had the virus, then something with her liver, or her kidneys – James has a way of speaking that spins off on all kinds of tangents, which he even apologized for “Sometime I lose my words,” he said.

So he described how they had given his mother a big surprise 70th Birthday Party (even though it was only actually her 69th). Family came from all around, a real family reunion, the kind you only get at a funeral, he said, but since they hadn’t wanted the reunion to be at her funeral, they decided to hold it now. They even had two cakes, one that said “69” and the other “70”

“Because my mother is special…”

His eyes teared up in a way that belied the simplicity of his words. Right there and then I decided if she would let me, that this would be my Mother’s Day Special.

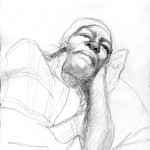

And so, I found myself last week sitting at the bedside of Claudette, a woman I had never met before and yet felt like I’d known, if not all my life, then in some essential way that didn’t require details of experience. She emanated a comfort – about herself, despite being ill (“Just draw me as I am, I don’t mind”) and about me, despite being a complete stranger, and about her kids who would come in and out as I sketched.

First her son James lay on the bed beside her for awhile. When he answered the phone, he told the caller, “Mom’s having her portrait done,” just as if he were saying “Mom’s having her hair done.” And then her daughter Tabitha introduced herself saying “I might not look like a daughter, but I am Claudette’s daughter” and indeed at first glance she appeared to be a handsome, dapper young man (“I wear boxers, and I wear them tight!”)

I asked Claudette how many children she had. She said five, but then explained there were four – James was the oldest, then I am not sure of the rest of the order. But her youngest son she said, had been killed three years ago. I said I was very sorry, that it must be the worst kind of pain, and as a parent myself I couldn’t imagine anything worse. I didn’t want to ask how he’d been killed, so sat and sketched, the silence eddying between us till it found words.

“I had wanted to make the trip down there,” at last she continued. “But I was in the hospital at that time and the doctor said, ‘Ms. Jackson, you aren’t well enough to make this trip.’ Still, I just wish I could have asked them, ‘How can you take something that can never be given back?’ I just wish I could know that, so that I could have some – what’s it called, I can’t remember, what’s the word?”

Her thoughts flowed again into realms that had no words, the way her son’s sometimes did, and mine followed.

“Peace? Peace of mind?” she ventured, but then said, “No, not peace. Closure. That’s the word I wanted to say. But I don’t have it.” She paused. “Life goes on. But I don’t have closure.”

There was much more in the two hours I spent with her and her family, bits of interactions, details of information, each in themselves slight or fleeting, but woven together in a rich complexity of wordless lines.

Another day he came back and spent some time drawing. He said he mostly drew cartooning, not much from observation, though his high school art teacher had encouraged him, and clearly he was capable. We looked at some of Leonardo DaVinci’s drawings and talked about how drawing could be a way of analyzing the world, that Leonardo was interested in figuring out human proportions, the structure of the human body, and so forth. Julien said that he was thinking of studying to be a medical technician, that his father in particular thought this would be a good idea, “Because people are always going to get sick, and need to be taken care of.”

Another day he came back and spent some time drawing. He said he mostly drew cartooning, not much from observation, though his high school art teacher had encouraged him, and clearly he was capable. We looked at some of Leonardo DaVinci’s drawings and talked about how drawing could be a way of analyzing the world, that Leonardo was interested in figuring out human proportions, the structure of the human body, and so forth. Julien said that he was thinking of studying to be a medical technician, that his father in particular thought this would be a good idea, “Because people are always going to get sick, and need to be taken care of.”